|

|

PEARLS AND OCCUPIED JAPAN

|

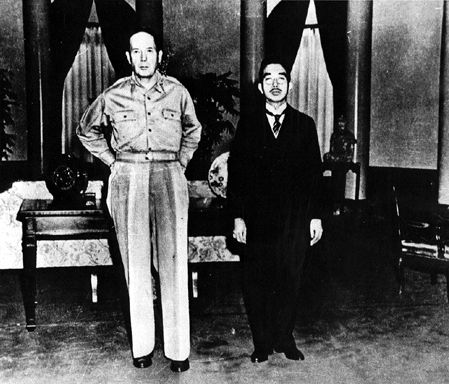

Image: A few days after the surrender of Japan to Allied forces, a diminutive Hirohito paid a visit to General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces. MacArthur arranged for this one photo to be taken, sending that the Japanese people an indisputable message that their Emperor was, in fact, a small man, and leaving no doubt about who was in charge. Later, on the Battleship Missouri, a formal ceremony would be held in which representatives of the Emperor would sign documents of surrender. Hirohito was spared execution for his war crimes, because the Allies felt that as a purely symbolic Emperor, he could be useful to them in carrying out their plans for post-war Japan. Under MacArthur's tutelage, Hirohito announced that he was not a god, but merely a normal man. MacArthur and the Americans prepared a new Constitution for Japan which is still in use today

|

![]()

When the war ended and the Allied Occupation Forces came to Japan, they classified cultured pearls as ?valuable and easily negotiable articles of commerce? considering them ?a potential avenue for illegal trading.? Measures were therefore taken to prevent unlawful trafficking. On January 14th, 1946, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, General Douglas Macarthur, sent a memorandum to the complete inventory of commercial stocks of pearls? and it prohibited all transactions except those under current contracts. It also required ?that all future transactions must receive the written authorization of General Headquarters.?

Three months later, on April 13th, 1946, the Supreme Commander

issued anoth?er directive to the Japanese Imperial Government, this time

stipulating the quantities of pearls to be supplied each week to the Army

Exchange Service. And on May 17 of the same year, domestic transactions of

pearls were prohibited at all distribution lev?els including retail shops. This

prohibition in effect terminated the sale of cultured pearls to Japanese

nationals. Cultured pearls thus became ?items of foreign trade, not essential to

the Japanese internal economy?? These prohibitions remained in force until

1948.

Three months later, on April 13th, 1946, the Supreme Commander

issued anoth?er directive to the Japanese Imperial Government, this time

stipulating the quantities of pearls to be supplied each week to the Army

Exchange Service. And on May 17 of the same year, domestic transactions of

pearls were prohibited at all distribution lev?els including retail shops. This

prohibition in effect terminated the sale of cultured pearls to Japanese

nationals. Cultured pearls thus became ?items of foreign trade, not essential to

the Japanese internal economy?? These prohibitions remained in force until

1948.

Thus, during the early years of postwar Japan, all production of the Japanese cultured pearl industry was sold through the Army Exchange Service to the Occupation Forces or exported to the United States.

Most of the pearls were made into 3.5 momme ?graduation? necklaces. Tens of thousands of these ?standard? necklaces found their way to the United States through the servicemen who brought them home as souvenirs for their mothers, wives or girl?friends. Probably unknown to the Japanese at the time, this was the best publicity cultured pearls could ever hope to have; it marked the beginning of their wide popularity in the United States.

As the years passed Japan?s cultured pearl industry regained some of its lost ground. A shortage of materials, oyster stocks and funds, however, hampered the speedy recovery of the industry, and its reputation as a minor player producing only luxury items continued. Obviously, Japan had other priorities as it tried to rebuild itself during the chaos that followed the war. In 1948, the number of pearl farms was still only 105, all of them operating on a greatly reduced scale.

But as it struggled, the Macarthur administration actually provided support in the restructuring of the pearl industry by implementing western methods and by helping to establish the Pearl Research Laboratory. From 1948, the Japanese govern?ment and other institutions also joined in by providing substantial financial support as the industry?s growth potential became increasingly obvious.

In 1948, The Allied Occupation Forces liberalized the trade of cultured pearls, reopening the door to both the domestic and international markets. Between 1948 and the early 1960s, Japan?s Akoya industry was still living almost entirely off the pro?duction and export of ?3.5 momme graduation necklaces?? The most popular ?grad?uations~? delivered by the thousands, had a wholesale price of $7.00 per strand, the equivalent of ~2,520 at that time. Higher quality necklaces which were also very pop?ular fetched $10.00 to $20.00 (Y3,600 to ~7,200).

For comparison, a Japanese male university graduate hired by a Japanese company in 1953 would receive a starting salary of approximately ~4,500 a month. (The large trading houses, however, such as Mitsui or Sumitomo might pay as much as ~6,000.)